Provenance: Back in the 90s I collected all the Call of Cthulhu Fiction line from Chaosium that I could get my hands on. They were excellent compilations of not only authors contributing to the Cthulhu Mythos but new pieces that expanded out the mythos. One of the books in the collection was The Complete Pegāna, which collects this book with a second novel by Lord Dunsany, Time and the Gods from 1906, and three additional stories from 1919. I'm just going to think about the first published book as a separate entity, and may come back to the others later.

The reason I've suddenly had an interest in Dunsany comes from discussions with Sacnoth, better known as Dr. John Rateliff. John had written his dissertation on Lord Dunsany, and I've become fascinated by the man and his work as a result. So here goes.

Review: Lord Dunsany is one of the forgotten master of fantasy, invoked but rarely read. Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany, was a larger-than-life individual. Nobility, he served in three major wars and was wounded in the Easter Rising. His domain was a castle in Ireland, on the borders of the Pale, which was the English-controlled zone of the island (think of it as a big Green Zone). He ran for Parliament and went on African safaris. He was a master at chess and pistols. Were he alive today (he died in 1957), he would have starred in those Dos Equis beer commercials.

The original Gods was self-published and was well-received, and Dunsany went on to write a number of fantasies, plays, and novels, including The King of Elfland's Daughter, for which he is best -known. But he gets full marks for being one of the first fantasy world-builders with Gods. Unlike previous recordings of legends, folk tales, and faerie stories, Pegana was about the creation and evolution of a imaginary world. |

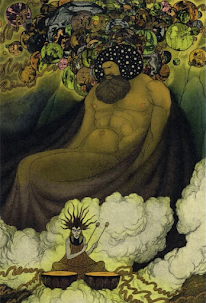

| MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI |

The stories are all incredibly short and literary. Dunsany's language is lyrical and poetic, filled with repeated language and pacing. It has the vibe of the Burton translation of the Tales from the Arabian Nights. Dunsany starts with a description of MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI, the ultimate creator, who creates smaller gods, then goes to sleep, lulled into slumber by Skarl, his drummer. Dunsany then moves to these small gods - Demiurges who create the world and humanity, then to the extremely localized home gods that make their abode on Earth, and from them to the priests, and to the prophets, and at last to the various kings, before circling back to speak of a very quiet Ragnarok. There is not of expository material here, and much is left hanging (is Skarl the Drummer a small god or something else entirely? Is one set of home gods different from another?), but the language is excellent - it feels good to be read aloud.

Dunsany, interestingly, has a decidedly cynical attitude towards his gods, priest, and kings. His gods fear when MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI will awaken and clear the deck of people, worlds, and small gods. The Priests interpose themselves between man and god and say that only through their organization can their prayers be truly heard (and that keeping those jobs is a priority). And the kings themselves often make remove those priests that get in their way and don't say what it is expected.

The connection with Lovecraft can be seen in the crafted cosmos with an uncaring overgod - Azathoth is surrounded by his court of demonic pipers much as MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI by his drummer. But Dunsany's smaller gods are much more aware of humanity and use them to play their godly games. The connection to Tolkien, though tempting, feels more tenuous - The professor's approach to creation seems further apart than the Dunsany/Lovecraft version, and is more deeply imbedded in the mythology that was Tolkien's preference.

Ultimately, Dunsany is remembered as that distant uncle in fantasy's family tree. Important when mentioned, his name invoked among the founders, but otherwise left alone. And the interesting thing is that in creating the first mythos, the first collection of original gods and their stories, he laid the groundwork for the fantasists to come.

More later,